Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

GPS Spoofing and the Risk to Maritime Navigation –

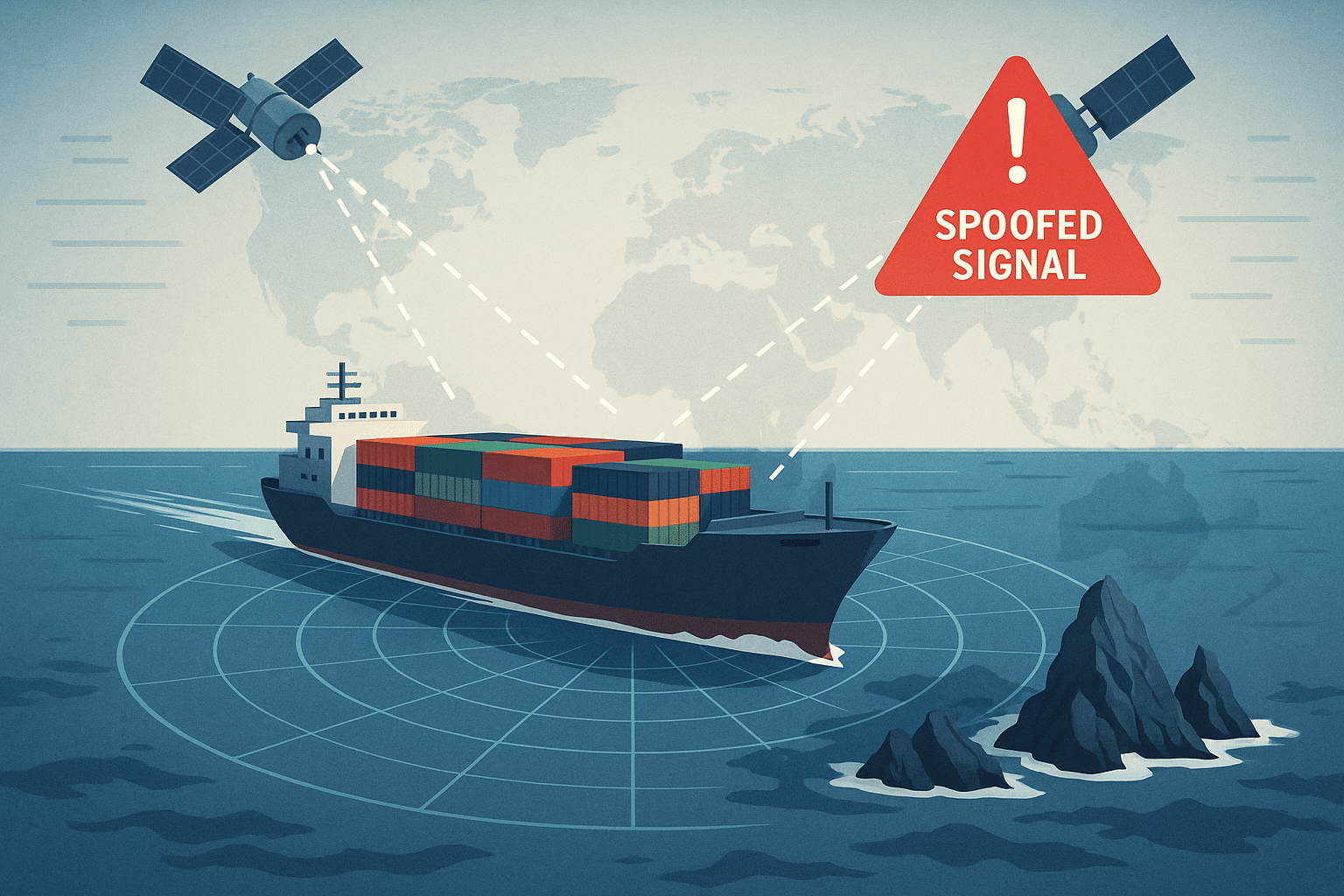

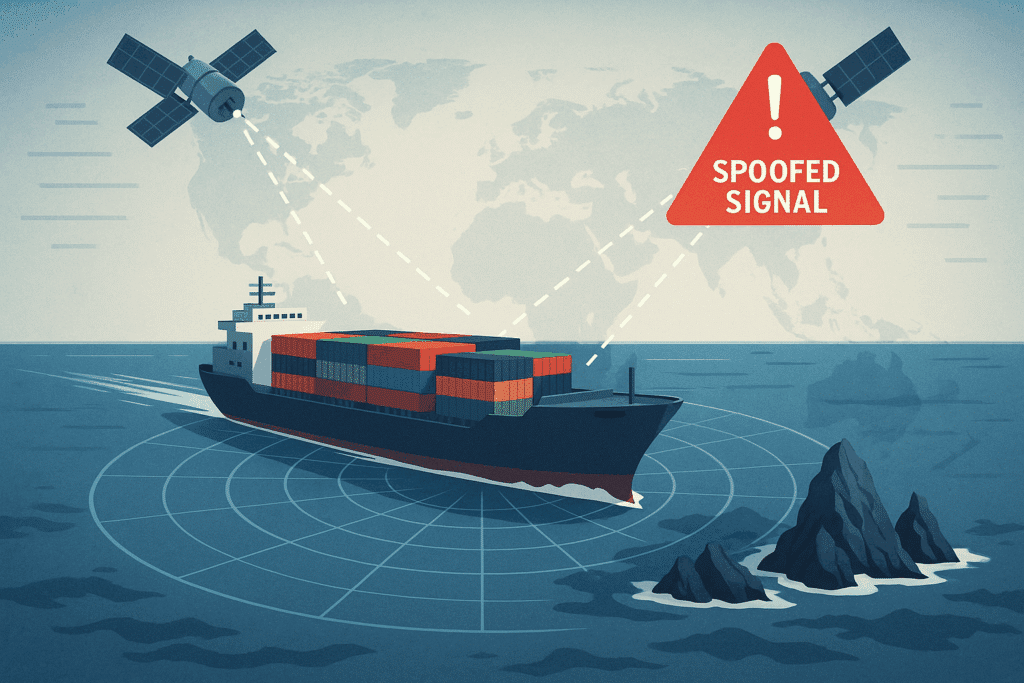

A new report from the Association of Average Adjusters examines the murky intersection of cyber exclusion clauses and modern maritime threats like GPS spoofing. GPS spoofing involves the transmission of fake navigation signals that mislead a ship’s systems about its real-time location. The result? A vessel may believe it is navigating safely in deep water while drifting toward grounding or collision.

This digital deception is dangerous. Spoofed signals can override Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), feeding false Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) data to a ship’s integrated systems. Human watchkeeping is expected to catch such errors, but in practice, crews often rely heavily on digital instruments.

Hull Policies Offer Coverage Until Cyber Clauses Intervene

Traditionally, accidental groundings fall under the umbrella of perils covered by standard Hull and Machinery (H&M) insurance. Even if crew error contributes to the incident, insurers are still liable under marine law unless willful misconduct can be proven.

But cyber exclusion clauses, especially models like LMA5403, change the equation. These clauses deny coverage for losses “directly or indirectly caused” by electronic systems used “as a means for inflicting harm.”

Spoofing involves an electronic system. That triggers the exclusion language. Whether it constitutes a “means of inflicting harm” depends on legal interpretation and case-by-case facts.

The Legal Grey Area: Harmful Intent and Burden of Proof

One of the thorniest issues in applying cyber exclusion clauses is determining motive. If spoofing occurs in a geopolitical hotspot—such as near contested waters courts may infer hostile intent.

In that case, the burden shifts to the shipowner to prove otherwise. But suppose the spoofing happens in a low-risk zone. In that case, insurers may need to identify the attacker and prove intent, an almost impossible task in most real-world cases.

Causation further complicates matters. Exclusions don’t just apply to events that directly cause a loss. The clause’s broad language includes losses “indirectly caused” or merely “contributed to” by digital interference. That standard opens the door for insurers to invoke the clause even when spoofing plays only a supporting role.

Get The Cyber Insurance News Upload Delivered

Every Sunday

Subscribe to our newsletter!

The Spoofing Timeline Matters

The report stresses that each incident must be judged on its facts. If a ship grounds hours after the spoofing event—across multiple watch changes—then the electronic deception may no longer be causally relevant.

Conversely, suppose spoofing is active during critical navigation decisions. In that case, it becomes harder for policyholders to claim it didn’t affect the outcome.

Watchstanding regulations, such as those set by the STCW Convention, expect navigators to verify GPS data using other instruments. But even failure to follow such protocols doesn’t automatically void a claim—unless cyber exclusion clauses apply.

WATCH – Maritime Supply Chain Cyber Risk – Shipping “Easy Target”

Buy-Back Clauses: One Way Out

To close the coverage gap, some insurers offer cyber “buy-back” clauses. These endorsements restore coverage for losses caused by spoofing and similar incidents, regardless of motive or attribution.

Buy-backs offer clarity but come at a premium. Not every shipowner chooses to pay for that certainty. As spoofing incidents grow, more stakeholders may consider cyber-specific endorsements essential to modern maritime risk management.

The Collision Between Old Insurance Logic and New Cyber Threats

This report exposes a deeper problem: the growing misalignment between traditional marine insurance logic and today’s hybrid threats.

Cyber exclusion clauses, once intended to protect insurers from unquantifiable tech risks, now frequently collide with physical maritime events like groundings. Spoofing sits in this intersection, where digital interference leads to tangible damage.

Insurers and insureds must adapt. Contracts must evolve. The lines between cyber and physical risks have blurred, and with them, the once-clear definitions of coverage. Proactive policy reform and clearer definitions are no longer optional; they’re essential.